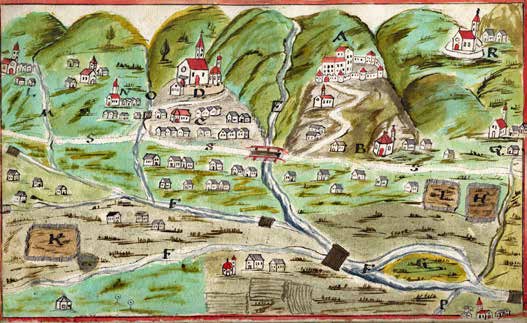

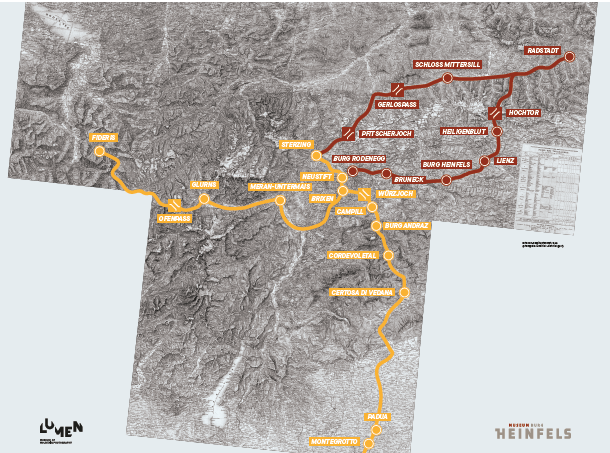

Escape routes, Michael Gaismair, 1525/26

Escape routes, Michael Gaismair, 1525/26

Michael Gaismair, born in 1490 in Tschöfs near Sterzing, evolves from a reformer into a revolutionary against the secular and ecclesiastical authorities in Tyrol. In October 1525, he is forced to flee: First via Bozen, Merano, Glurns, and the Ofen pass to Fideris in Graubünden, Switzerland. After returning to Sterzing, he has to escape once again. With his followers, he crosses the Pfitscher Joch pass into the Ziller valley, then over the Gerlos pass and as far as Radstadt in the Salzburg region. On 2 July 1526, however, he is forced to abandon the siege of the city. On his retreat, Gaismair attempts to re-enter the Tyrolean Puster valley with a force of about 2,000 men. His path leads over the Hochtor pass, past the Großglockner and Pasterze glacier to Heiligenblut in the Möll valley of Carinthia, then via Lienz, Heinfels castle, and Bruneck to Rodenegg castle. But the pressure becomes too big, and Gaismair, with his remaining 1,000 fighters, moves southward, over the Würzjoch pass, through Campill and Andraz castle into the Cordevole valley, placing himself under the protection of the Republic of Venice. He settles in the Villa Draghi in Montegrotto. On 15 April 1532, he is murdered in Padua.

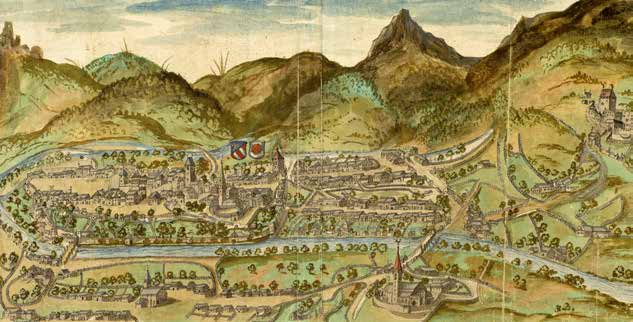

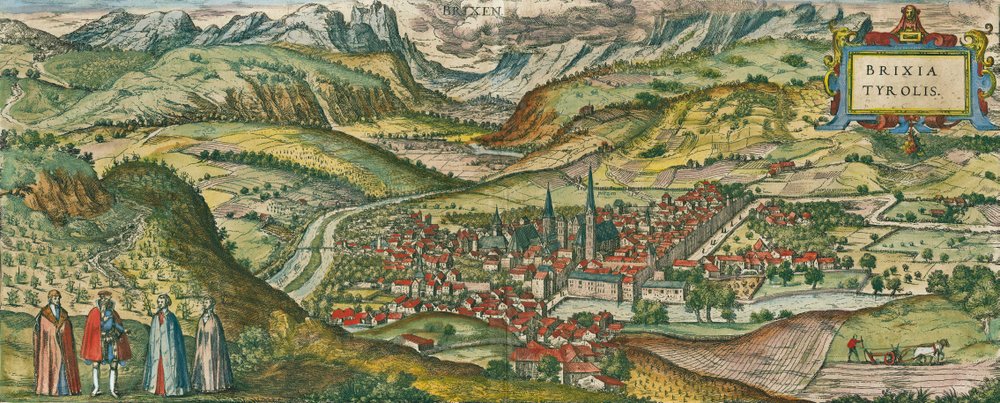

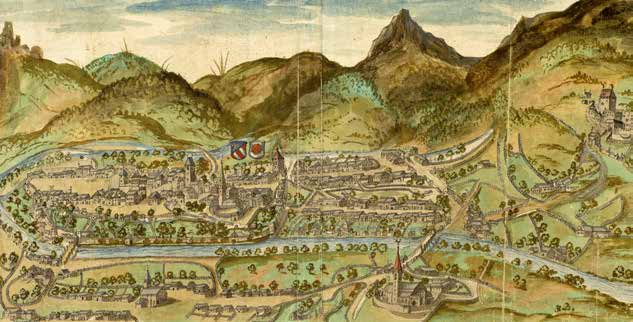

Brixen (“Brixia Tyrolis”), 1580

(Coloured copperplate engraving; Alexandra Überbacher Collection - TAP)

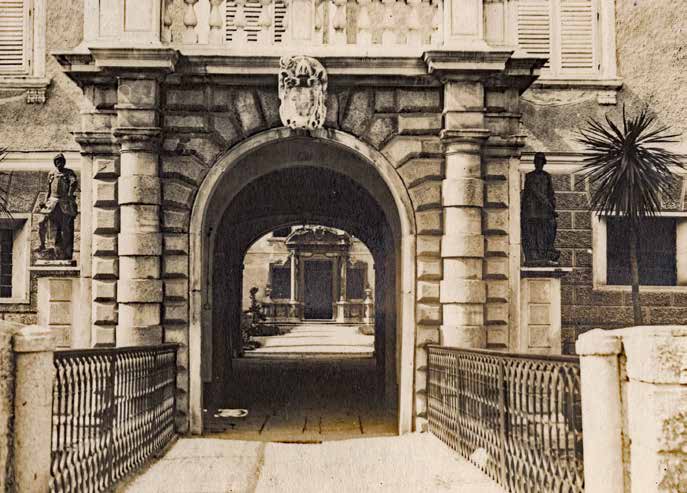

The entrance to the Hofburg of the Prince-Bishopric of Brixen was stormed by rebellious peasants on 10 May 1525. Photo taken ca. 1916.

(Photographer: Unknown; Collection Isabelle Brandauer—TAP)

Neustift monastery is looted by insurgents in May 1525. Photo taken in 1902.

(Photographer: Raimund von Klebelsberg; Collection Klebelsberg, Institute for Geology, University of Innsbruck—TAP)

St. Vigil in Untermais, looted by the peasant army in 1525 (ceiling fresco in St. George’s Church, Merano, 1765). Photo taken in 2022.

(Photographer: ManfredK; Wikipedia, CC BY 4.0)

Glurns, July 2024

(Photographer: Richard Piock)

Ofen pass summit (2,155 m): view into the Münster valley toward the Ortler, ca. 1950

(Photographer: Otto Furter; Collection Richard Piock—TAP)

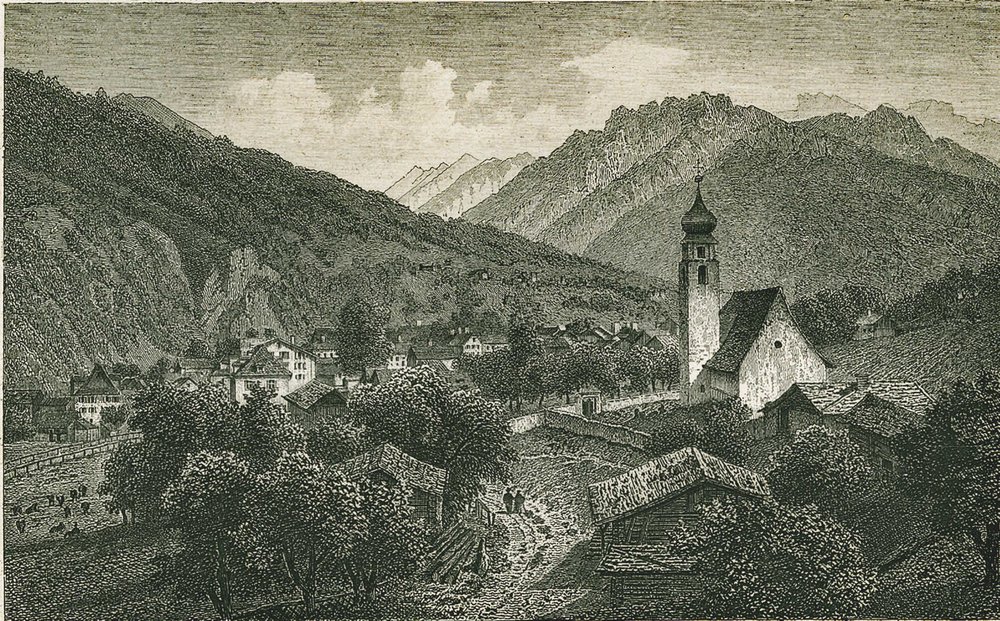

Bad Fideris and Fideris village in Graubünden/Switzerland, ca. 1880

(Druck und Verlag G. G. Lange; Archive Richard Piock)

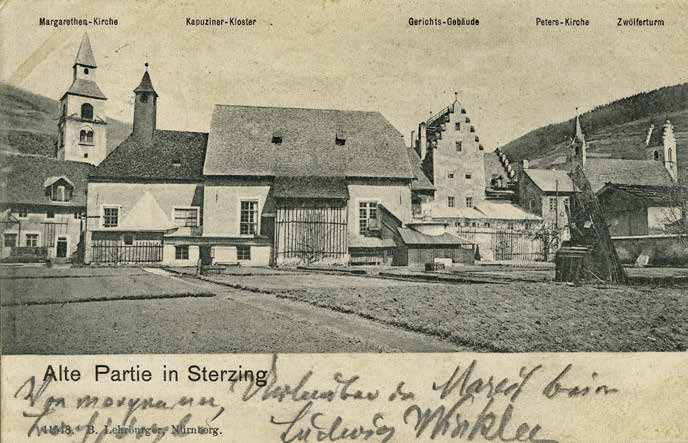

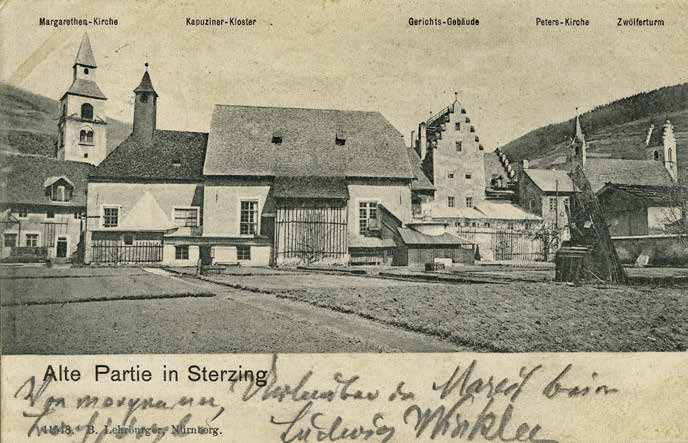

Historic buildings in Sterzing, ca. 1900

(Photographer: Bernhard Lehrburger; Collection Monika Weissteiner, Stadtarchiv Bruneck—TAP)

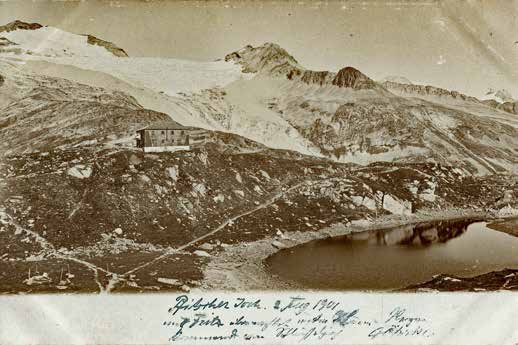

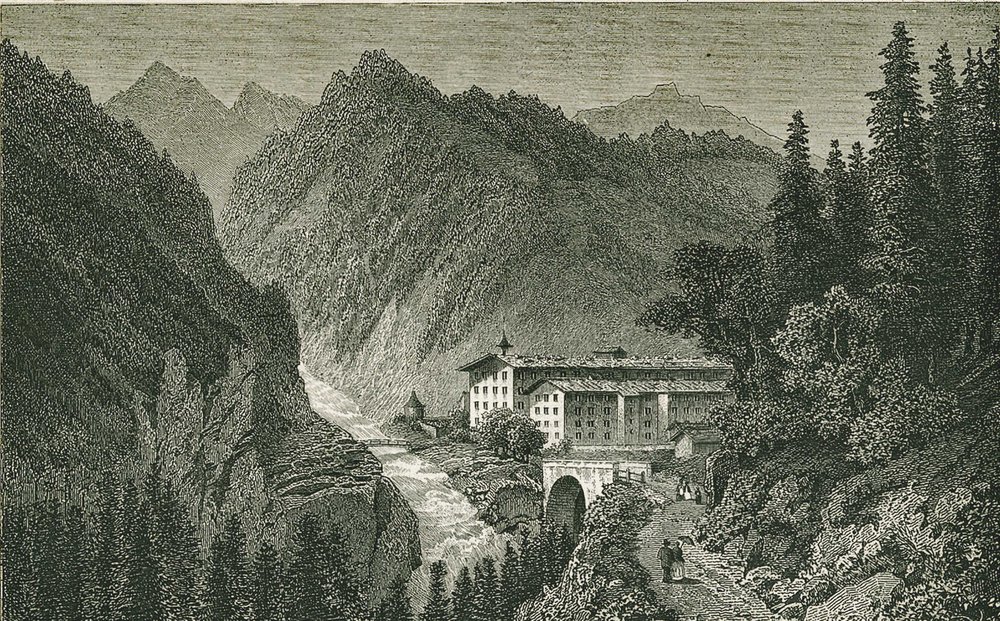

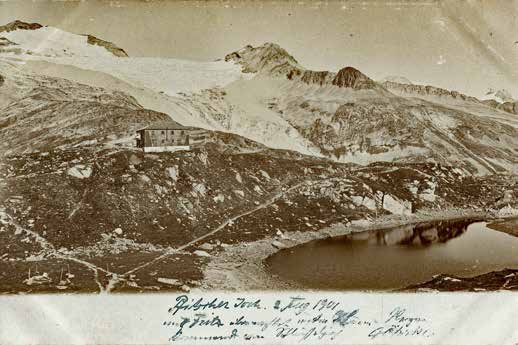

In early May 1526, Michael Gaismair flees across the Pfitscher Joch pass into the Zillertal valley. Photo taken in 1901.

(Photographer: Unknown; Collection Richard Piock—TAP)

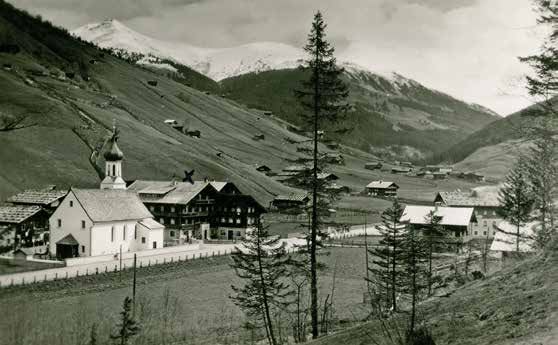

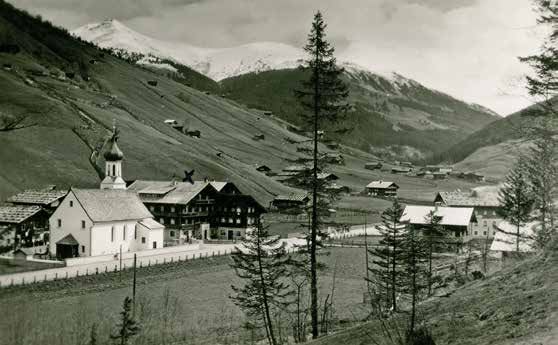

Gerlos, towards the summit of the pass, ca. 1935

(Photographer: Karl Dornach; Archive Martin Kofler)

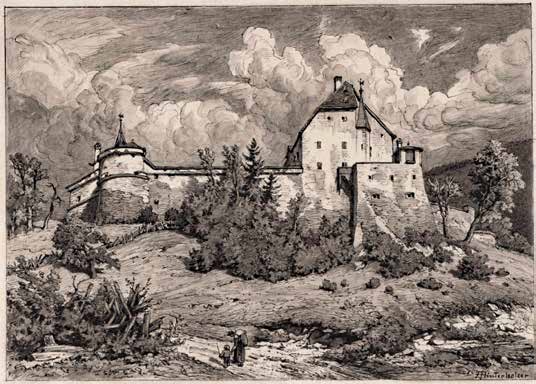

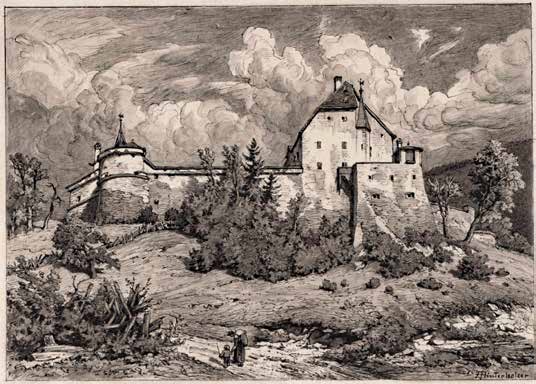

Mittersill castle is looted by insurgents in 1525/26. Pen drawing, 1889.

(Franz Hinterholzer; ÖNB)

Radstadt is besieged for weeks by Gaismair’s peasant army. Photo taken ca. 1940.

(Photographer: Franz Lenz; Collection Richard Piock—TAP)

In early summer 1526, Michael Gaismair crosses the main Alpine ridge with around 2,000 men via the Hochtor near the Großglockner. Photo taken ca. 1910

(Photographer: Unknown; Collection Richard Piock—TAP)

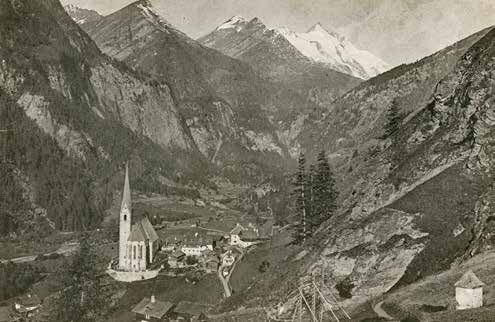

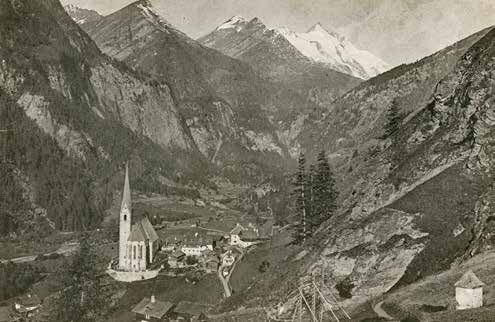

Heiligenblut with the Großglockner, 1893

(Verlag Römmler & Jonas; Collection Stadtgemeinde Lienz, Archiv Museum Schloss Bruck—TAP)

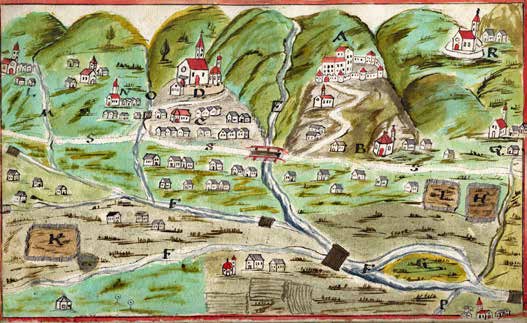

Lienz, 1606/08, watercolor. As promised, Lienz is not looted by Gaismair and his army in early July 1526.

(From: Matthias Burgklechner, Der Tiroler Adler; Österreichisches Staatsarchiv/Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv)

The stately castle of Heinfels, ink drawing with watercolor, 1750. Gaismair’s army tries unsuccessfully to capture the castle.

(Leopold Matthias Spielmann; Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum)

Bruneck, ca. 1700

(Hand-colored engraving; Collection Alexandra Überbacher—TAP)

Aerial photo of Rodenegg castle, 2010

(Photographer: © Ralph Mittermaier)

The Würzjoch pass (1,982 m) broadly connects the Gader valley with the Eisack valley. Photo taken in 2014.

(Photographer: Manfred Glueck, 2014, Alamy Stock Photo)

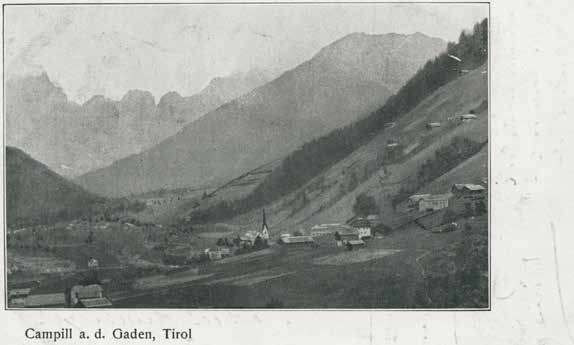

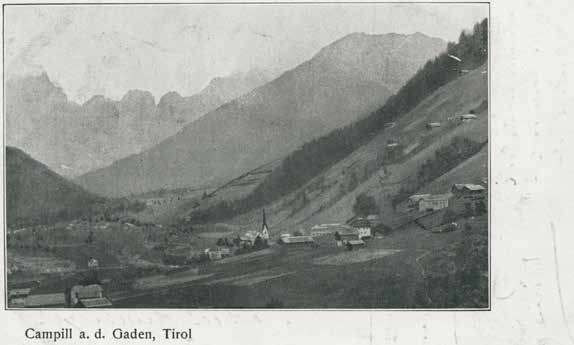

Campill an der Gaden, ca. 1910

(Photographer: Unknown; Collection Georg Schondorf—TAP)

Andraz castle, south of the Falzarego pass, ca. 1915/16

(Photographer: Unknown; Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, Rome)

Cordevole valley, gorge of Muda, 1907

(Photographer: Pompeo Breveglieri; Collection Cartoline dall’Agordino, LAIM 298)

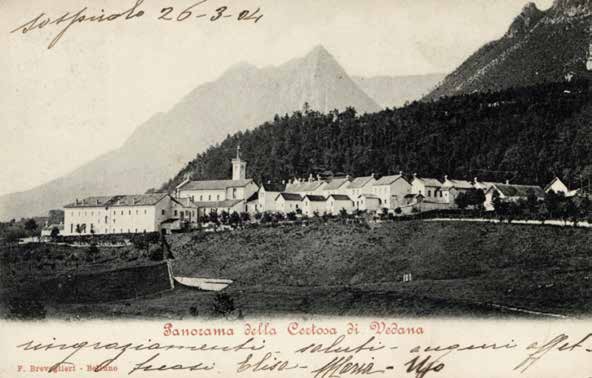

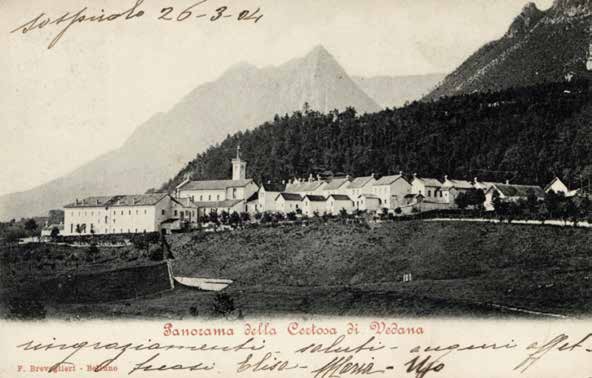

Certosa di Vedana, 1905

(Photographer: Pompeo Breveglieri; Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, Rome)

Montegrotto, ca. 1950. Michael Gaismair lived here for several years in the Villa Draghi.

(Photographer: Unknown; Collection Richard Piock—TAP)

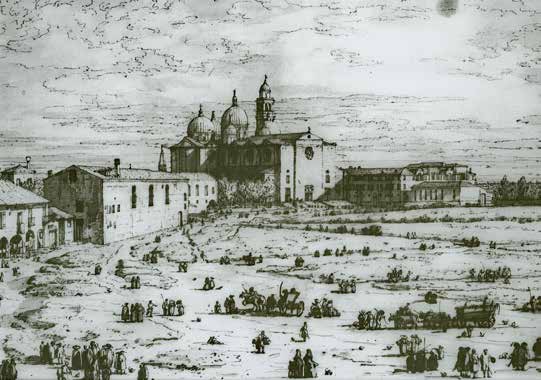

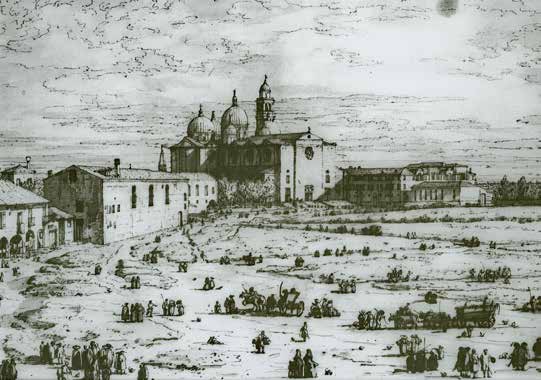

Padua, Prato della Valle with S. Giustina church, 1740

(Reproduction of an etching by Giovanni Antonio Canaletto; Archive Richard Piock)

Escape routes, Michael Gaismair, 1525/26

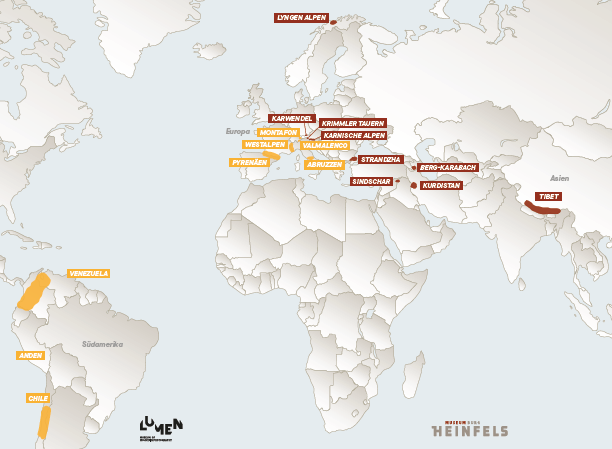

Escape routes, 20th and 21st century

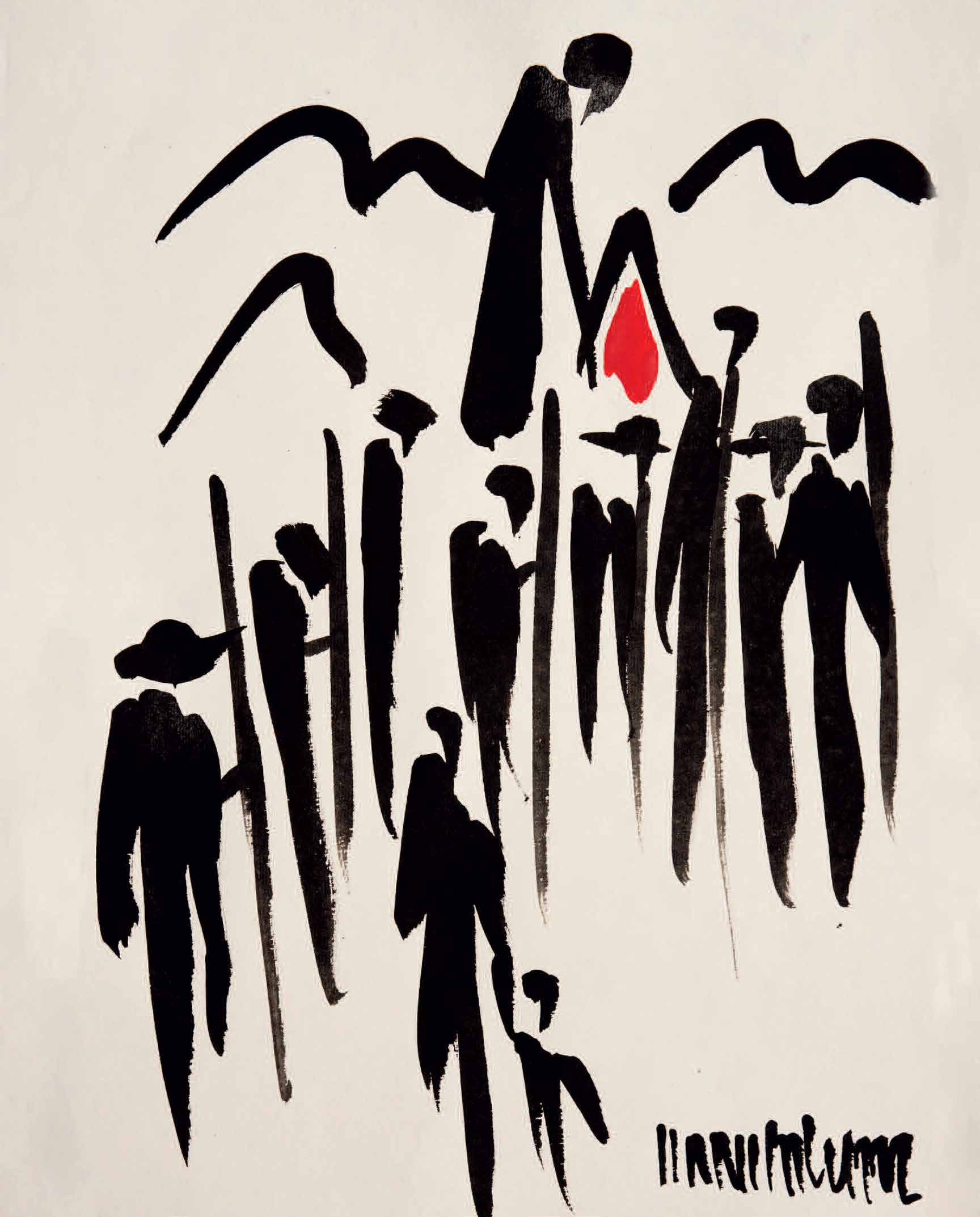

The Escape Routes of Michael G.

Across the mountains—in pursuit of freedom—from 1525/26 to the present day

Across the mountains—in pursuit of freedom

(Hans Salcher, Ink on handmade paper, 2024)

When political power threatens the freedom and equality of cultural or religious minorities, seeking refuge in the mountains as a natural exile or crossing them in search of safer ground has been a common recourse throughout history. This has held true for over 500 years, even in today’s digital age.

This exhibition presents the historical escape routes of Michael Gaismair and his army in 1525/26 through images and photographs, alongside more recent escape routes from the 20th and 21st centuries. They are shown at two exhibition sites, located west and east of Bruneck: At LUMEN. Museum of Mountain Photography on Kronplatz, the focus is on Graubünden, the Gader valley, and Padua, as well as Chile, the Pyrenees, and the Western Alps. At Heinfels Castle, the focus shifts to the Ziller Valley, Salzburg, and East Tyrol, along with the Krimmler Tauern, Iran, and Tibet.

Imprint

Curators: Richard Piock/Martin Kofler (Tyrolean Photo Archive TAP)

Design: Atelier Roland Stecher, Götzis/Aberjung, Dölsach

Display elements: Schösswender, Anras/Tischlerei B+Z, St. Lorenzen/Leitner_Ausstellungssysteme, Burgdorf

Print: gamma3, Sillian/Bluepuma, Lienz

Nagorno-Karabakh 2023

Flight of the Armenians with all their belongings from Nagorno-Karabakh following the Azerbaijani military offensive—here already near Kornidzor, Armenia, 29 September 2023

(Photographer: Anatoly Maltsev; EPA Images (European Pressphoto Agency))

The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, a region of 4,400 km² located in the former Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan but predominantly inhabited by Armenians, has been smoldering for decades. While the Armenians strive for national self-determination, Azerbaijan seeks to fully reintegrate the region into its national territory. After several wars since 1988 with varying outcomes and tens of thousands of casualties on both sides, Azerbaijan’s army under President Ilham Aliyev succeeds in occupying one-third of the territory in 2020. On 19 and 20 September 2023, Azerbaijan launches a military operation that results in the complete recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh. Almost the entire Armenian population of the region—around 120,000 people—is displaced and flees, many of them across the mountains of the Lachin corridor, the only land link between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Azerbaijan soon begins initial steps to resettle Azerbaijanis who were expelled from the region during the 1990s. According to President Aliyev, the conflict is now over …

Children of Armenian refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh with their few belongings during a break in Goris, Armenia, the next larger town after the Lachin corridor, 28 September 2023

(Photographer: Anthony Pizzoferrato; picture alliance/Middle East Images)

Armenian refugees boarding a bus in Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital, Stepanakert, 20 September 2023

(Photographer: unknown; Russian Ministry of Defense, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0)

Armenians after fleeing Nagorno-Karabakh, 21 September 2023

(Photographer: unknown; Russian Ministry of Defense, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0)

The genocide of the Yazidis, Sinjar, Iraq 2014

Faysh Khabur bridge over the Tigris river on 10 August 2014

(Photographer: Khalid Mohammed; AP/picturedesk.com)

In August 2014, the Yazidi minority is forced to flee from the Islamic State (IS) into the Sinjar mountains. After U.S. airstrikes on IS positions, several thousand Yazidis cross the Faysh Khabur bridge over the Tigris near the city of Sinjar in northern Iraq to reach the border with northeastern Syria. According to the United Nations, between 5,000 and 10,000 Yazidis are brutally murdered by IS. More than 7,000 Yazidi women and children—mostly girls—are abducted.

Children are forced to become fighters, women are held as sex slaves, raped, and abused. In 2016, the international community recognizes the crimes committed against the Yazidis as genocide. By mid-2019, around 70 mass graves are documented in the Sinjar region. However, up to 200 such graves are suspected to exist. In 2016, the international community recognizes the crimes committed against the Yazidis as genocide. In total, more than 400,000 Yazidis are displaced from their homeland. Many of them still live in camps in northern Iraq, where they lack access to clean water, electricity, schools, hospitals, and jobs.

Yazidi refugees at a newly erected camp, 15 August 2014

(Photographer: Khalid Mohammed; AP/picturedesk.com)

Yazidi protests outside the White House in Washington, D.C., 7 August 2014

(Photographer: Kaitlynn Hendricks; www.flickr.com/people/126516690@N08, CC 2.0)

Stuffed toys on a fence at a Yazidi mass grave near the Sinjar mountains

(Photographer: Benno Schwinghammer; AP/picturedesk.com)

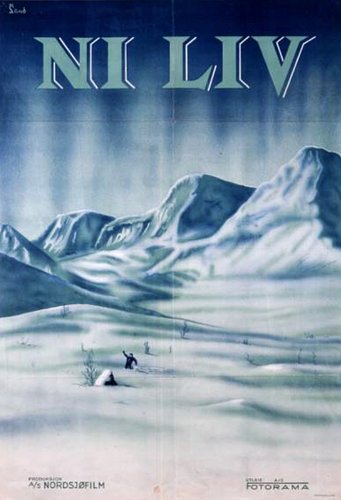

Jan Baalsrud, Lyngen Alps, 1943

The eastern slope of Jiehkkevárri mountain (1,833 m), where an avalanche buries Jan Baalsrud up to his neck, and Lyngsdalen village; photo taken in 2011

(Photographer: Simo Räsänen; Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

When Norway is occupied by the German Wehrmacht in April 1940, resistance begins to grow. In the spring of 1943, British-trained resistance fighter Jan Baalsrud (1917–1988) finds himself at the center of a legendary survival story. Baalsrud’s boat, loaded with weapons and explosives, is attacked and sunk by the Germans in Toftefjord bay in northern Norway. Of his entire commando, he is the only one to survive, as he manages to swim to shore and flee southeast across the snow-covered Lyngen Alps. His escape is harrowing: He is buried by an avalanche, survives a snowstorm, suffers severe frostbite, is blinded by snow, and endures relentless hunger. During his nine-week-long ordeal, he receives vital assistance from the local population. Eventually, Baalsrud is smuggled across the border into Sweden by sled. After a long recovery, he returns to Norway from Scotland as an agent and stays in Norway until the end of the war. His legendary escape makes it to the big screen twice: In 1957, titled “Nine Lives” (“Ni Liv”), and in 2017, titled “The 12th Man”.

Jan Baalsrud, ca. 1942

(Photographer: unknown; nordligefolk.no)

Movie poster “Ni liv” (“Nine Lives”), 1957

(www.cinemaclock.com)

Movie poster “The 12th Man”, 2017

(www.movieinsider.com)

Baalsrud Museum in Furuflaten, where the resistance fighter receives assistance from the locals; photo taken in 2012

(Photographer: unknown; Stiftelsen Jan Baalsrud)

Tina and Hasti, Kurdistan, Iran, 2022

Mountain region between Iran and Iraq near the Bashmaq border crossing, 2022

(Photographer: Alice Martins)

After Shah Reza Pahlavi is overthrown and the Islamic Republic of Iran is established under religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979, the first counter-demonstrations begin, and, just like later protests, they are swiftly broken up. Thousands of political opponents are executed, resistance is brutally crushed, and countless people are driven into exile, for example across the mountains of Kurdistan into northern Iraq. Just like the friends Tina and Hasti in 2022. Christoph Reuter reports their story in “Der Spiegel”, a German weekly news magazine. They are photographed by Alice Martins, the message: “As a woman, you are nothing in Iran”, says Hasti. During a demonstration, a boy is killed next to them: “That’s when I knew: I had to disappear.” 14 hours in the darkness, along rocky slopes, so that the beam of their flashlight wouldn’t betray them. Even smugglers say that the so-called “Revolutionary Guards” patrol the border mountains with drones and night-vision goggles and shoot without warning.

Iranian friends Tina (right) and Hasti (left) in a camp in northeastern Iraq, 2022

Mountain road near a refugee camp in northeastern Iraq, 2022

Bashmaq border crossing in Kurdistan, Iran, 2022

(Photographer, all images: Alice Martins)

Yangdol and Kelsang, Tibet 1995

Up the Gyabrag glacier with its bizarre ice formations in temperatures around minus 30 degrees Celsius.

(Photographer: Manuel Bauer; Agentur Focus)

In 1950, Communist China under Mao Tse-tung occupies Tibet. Nine years later, Tibet’s secular leader, the Dalai Lama, flees into exile in northern India. Tens of thousands of Tibetans follow him over the years, crossing the mountain passes of the Himalaya to the south. In March and April 1995, Swiss photographer Manuel Bauer accompanies six-year-old Yangdol and her father Kelsang on their harrowing, 22-day ordeal escaping from Lhasa in Tibet. Their route leads them across the 5,716-meter-high Nangpa La pass west of Cho Oyu (8,188 m), into Nepal, from where they continue on to the Tibetan exile community and the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India. Bauer’s work titled “Flucht aus Tibet” (“Flight from Tibet”), first published as a feature in July 1995, is released as a photo book in 2009. The powerful images bear witness to the extreme dangers and brutal suffering of those courageous enough to flee over the mountains—and commemorate those who did not survive the journey ...

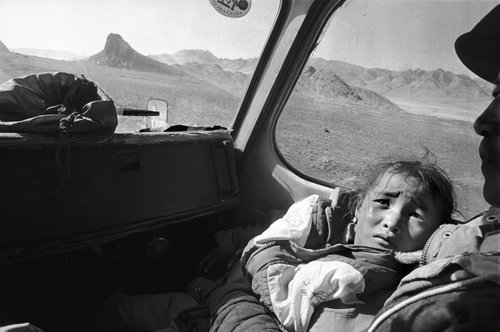

A lorry picks up Yangdol and Kelsang on their way to the Himalayas. Together with photographer Manuel Bauer, they pretend to be pilgrims ...

They continue on foot and cross a frozen river and the endless stone and ice deserts of the Himalayas.

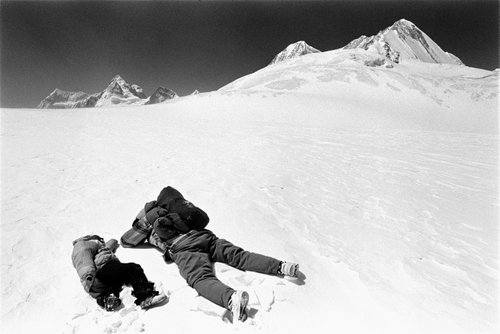

On day nine of their escape, they cross vast snowfields along the Kyetrak glacier—Cho Oyu (8,188 m) rising in the background.

The next day, they reach the Nangpa La (5,716 m), which separates Tibet from Nepal. The conditions are brutal. The altitude, the wind, the struggle to move through the deep snow: When you fall into the snow, you look as if life has left you.

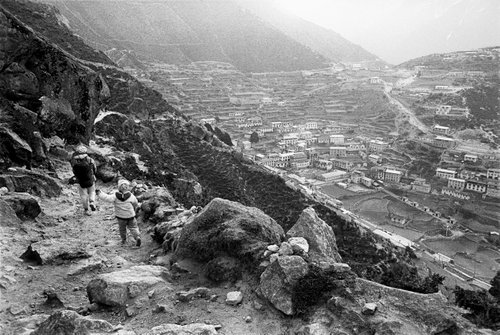

Finally, the first glimpse of Namche. The village in Nepal’s Khumbu region is known as the gate to the High Himalayas and a starting point for many expeditions to Mount Everest.

From Namche, a helicopter takes them to Kathmandu, from where they begin a three-day journey by refugee bus across the Indian border and on to New Delhi. After a 13-hour overnight bus ride, they reach Dharamsala, home of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, who welcomes the refugees from Tibet—among them little Yangdol.

(Photographer, all images: Manuel Bauer; Agentur Focus)

Jürgen Cyrulik, Strandzha mountains, Bulgaria, 1988

The Strandzha mountain range in southeastern Bulgaria, Burgas Province; photo taken in 2019

(Photographer: Ondrej Zvácek; Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

In the 1980s, at the height of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States, an increasing number of citizens of the GDR, the German Democratic Republic, attempt to flee the Communist dictatorship via Bulgaria. Until 1989, approx. 2,000 people escape via this route, either traveling alone or in small groups. Officially, they are holidaymakers, spending their vacation at the Bulgarian Black Sea like thousands of others. In reality, however, their goal is to cross the border into the European part of Turkey via the Strandzha mountain massif. Some 500 people manage to cross the border illegally, while many others are intercepted and handed over to the GDR’s secret police, the Stasi. Some are even shot and killed. Journalist Rayna Breuer has spent years researching this particular refugee route. One especially moving story she discovered is that of Jürgen Cyrulik, who attempts the escape via this route in 1988 but fails. 30 years later, he crosses paths again with Stoyan Todorov, the border patrol officer who arrested him back in the day ...

Holiday postcard from the Bulgarian Black Sea to the GDR, 1973 “Beautiful sunshine, a warm 27 degrees, and no jellyfish.”

(Photographer: unknown; archive Martin Kofler)

The Sunny Beach (Slantchev Briag) north of Burgas in Bulgaria, 1977

(Photographer: unknown; archive Martin Kofler)

Stanka Papazova grew up in this region and vividly recalls the time before 1989, when the Bulgarian border installations were still in operation; photo taken in 2019

(Photographer: Rayna Breuer)

Abandoned border structures between Bulgaria and Turkey, 2019

(Photographer: Rayna Breuer)

Documentary by Rayna Breuer “The GDR defector and the Bulgarian border guard”, Deutsche Welle, 2019, www.dw.com and www.youtube.com

Wilhelm Hoegner, Karwendel mountains 1933

Wörner peak in the Karwendel mountain range, 22 June 2020

(Photographer: Thorsten Darmstadt; Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

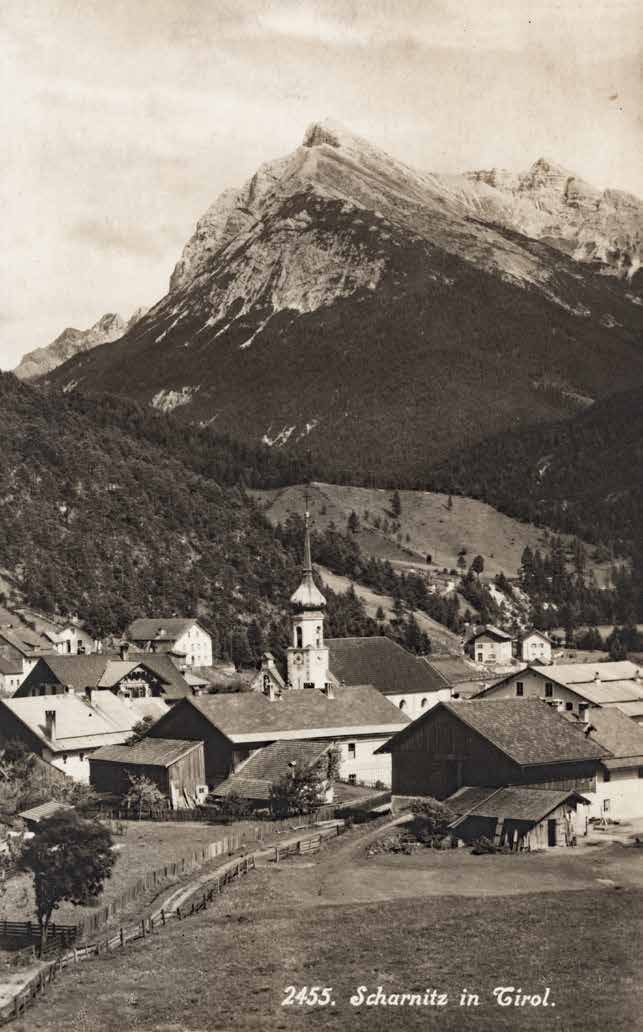

When the Nazis rise to power and Adolf Hitler is appointed as the new German chancellor on 30 January 1933, all other parties are banned or dissolved. Politicians from the outlawed parties are sent to newly erected concentration camps, tortured, and murdered. One of those who managed to escape is Social Democrat Wilhelm Hoegner (1887–1980), member of the German parliament from 1930 to 1933. Together with journalist and fellow Social Democrat Franz Blum and mountain guide Hans Fischer, he sets out from Mittenwald in Bavaria, Germany. During a thunderstorm, they cross the Karwendel mountains at Tiefkarspitze and Wörner (2,474 m) on 11 and 12 July 1933, climbing narrow trails and mountain ridges and crossing snowfields before reaching Scharnitz in Tyrol, Austria. From the Goldene Sonne, a hotel associated with the Social Democratic party, in Innsbruck, they continue on to Switzerland. After the war, Hoegner plays a key role in shaping post-war Germany—as one of the authors of the Bavarian constitution and as Minister-President of Bavaria (1945/46 and 1954–1957).

Wilhelm Hoegner, 1925

(Photographer: unknown; Archiv der sozialen Demokratie/Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn)

Wilhelm Hoegner, 1956

(Photographer: J. H. Darchinger; Archiv der sozialen Demokratie/Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn)

Scharnitz in Tyrol, Austria, ca. 1936

(Photographer: Ottmar Zieher; collection Peter Unterweger—TAP)

Goldene Sonne hotel in Innsbruck, Austria, ca. 1910

(Photographer: unknown; archive Martin Kofler)

The Lienz Cossack tragedy, 1945

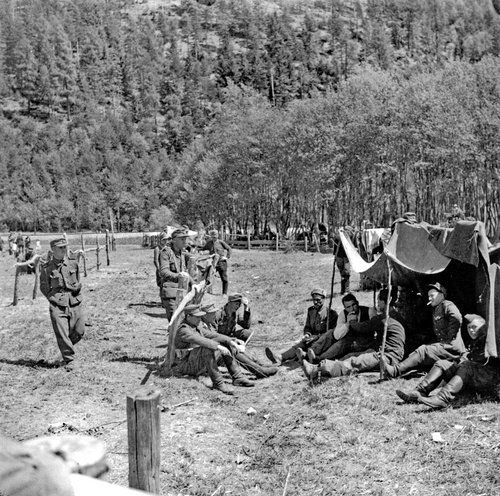

Cossacks marching in the Lienz valley, May 1945

(Photographer: unknown; Imperial War Museum, London)

The final days of the war are marked by chaos. Amid the collapse of the German Reich, a large group of armed Cossacks arrives in the Lienz valley on 4 and 5 May 1945, making their way from Tolmezzo in Italy across the Plöckenpass and the Gailberg. Approx. 25,000 men, women, and children along with several thousand horses find themselves in Lienz, a small town with no more than 8,000 inhabitants at that time. The anti-communist Cossacks, originally from the southern Soviet Union, align themselves with the German army following the occupation of their homeland and are involved in the brutal operations against the partisans in the Balkans and in northern Italy between 1943 and 1945. On 8 May 1945, British troops liberate the entire region and the town of Lienz, which is heavily damaged by U.S. air raids, ending Nazi rule. The fate of the Cossacks, however, had already been decided by the Allies at the Yalta Conference: All former citizens of the Soviet Union are to be extradited to the USSR. When the British forces start the forced return of the Cossacks on 1 June 1945 from the Peggetz district of Lienz, several hundred Cossacks die when a panic breaks out and many commit suicide. By mid-June, more than 22,000 Cossacks are repatriated to the Soviet Union.

One of many Cossack camps in May 1945, here at Nörsach in East Tyrol, near the border with Carinthia

(Photographer: unknown; Imperial War Museum, London)

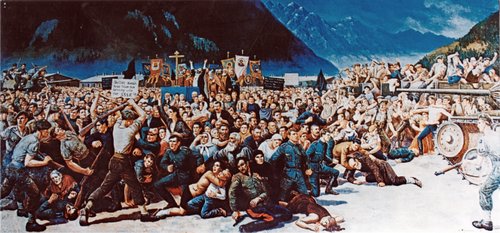

Realistic painting by Sergey Korolkov, an eyewitness of 1 June 1945 in the Peggetz district of Lienz, 1957, titled “Betrayal of the Cossacks at Lienz”

(Print in the collection of the municipality of Lienz, archive Museum Schloss Bruck—TAP)

Lienz Cossack cemetery in the Peggetz district, ca. 1960

(Photographer: Fracaro; collection of the municipality of Lienz, archive Museum Schloss Bruck—TAP)

Each year around 1 June, commemorative services are held at the Lienz Cossack cemetery, here in 1965

(Photographer: unknown; collection of the Lienz Veterans’ Society, eastern Tyrol—TAP)

Jewish refugees, Krimmler Tauern, 1947

View from the Krimmler Tauern towards the Ahrntal valley in South Tyrol; photo taken in 2009

(Photographer: Fipsinger; Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

After 1945, many Jews who survived the Nazi genocide, the Holocaust, and the antisemitic violence in Eastern Europe decide to leave Europe for good. More than 250,000 people flee via the mountains, many of them over the Brenner pass into Italy and from there on to Palestine. A secret Jewish organization called “Bricha” (Hebrew for “flight”) helps organize these escapes. Another escape route leads from the refugee camps in the U.S. occupation zone in the Austrian province of Salzburg across the Krimmler Tauern mountain pass (2,634 m) into South Tyrol, Italy. In the summer of 1947, approx. 5,000 people take this route into Italy and continue on to Palestine (“Eretz Israel”). The organization “Alpine Peace Crossing” commemorates this escape route with an annual commemorative hike starting at Krimmler Tauernhaus mountain hut and crossing the mountain pass into Kasern in South Tyrol. This year's hike will be held on 28 and 29 July 2025. However, the hike is already fully booked: https://alpinepeacecrossing.org/

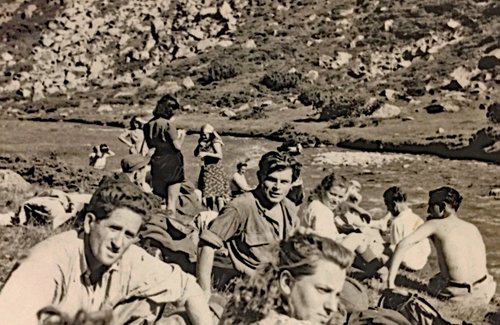

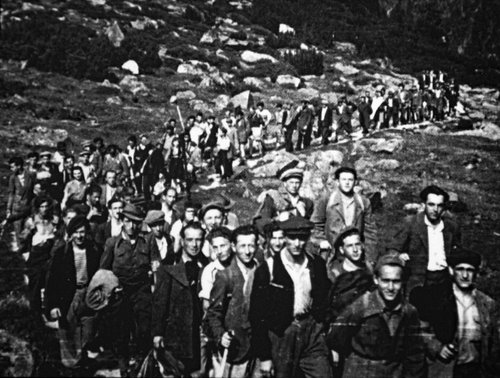

A stop at the Krimmler Tauernhaus before setting off, summer 1947

Up the mountain with a toddler and only the most necessary belongings, summer 1947

Taking a break, summer 1947

The ascent from the Krimmltal valley is a challenge for the inexperienced hikers, summer 1947

(Photographer, all images: unknown; Alpine Peace Crossing)

Commemorative plaque at the Krimmler Tauern pass; photo taken in 2011

(Photographer: Christina Nöbauer; Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

Krimmler Tauern with a marker for the Alpine Peace Crossing trail; photo taken in 2016

(Photographer: Whgler; Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)